Let me begin by saying that, clearly, no non-redheaded person is ever going to read Red: A History of the Redhead by Jacky Colliss Harvey. I officially recommend this book, but…come on. It’s inside baseball. I’ll give you the highlights from a redhead’s perspective, and if you don’t end up picking up a copy, at least you can be nicer to the redheads in your life, okay? We’ve been going through it for most of human history.

1. Redheads have put up with a lot.

As the title implies, this book winds through redheaded history from Neanderthals to Elizabeth I to Dana Scully. It’s sprawling. And the one constant throughout all eras is that being a redhead comes with baggage.

For women, some of it is advantageous. Red hair can signal fertility, evolutionarily speaking (see #2), and so we get all the redheaded sex bombs of modern cinema–Joan Holloway, Natasha Romanoff, Jessica Rabbit. In the ancient world, red hair also signaled being a bloodthirsty Viking and/or Celt, and from there we get the fiery, spunky girl stereotype, too–Anne of Green Gables, Pippi Longstocking, Caddie Woodlawn.

But much of it is not advantageous at all. We are notorious for having bad tempers, supposedly (especially if we point out what a moron you are for thoughtlessly spewing this sort of noninformation), and the details of our redheaded bodies have been matters of male adolescent discourse for centuries.

Similarly, redheaded women have an association with prostitution, thanks to some very weird historical gymnastics around Mary Magdalene and a whooooooole bunch of Pre-Raphaelite paintings.

Redheaded men don’t fare much better. Prince Harry, Michael Fassbender, Sam Heughan, and BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH, for the love of God (I learned he was a redhead while reading this book and shan’t recover), have only recently offered an alternative to the ugly, brutish, or foppish redhaired man of the last thousand years or so.

For most of history, they’ve been either run out of villages or beaten up on playgrounds. That’s partially because of the barbarian thing, partially because of anti-Semitism, and partially because of South Park. I know I never heard the word ginger in a non-vegetal context until “Ginger Kids” aired 2005, but I haven’t stopped hearing it, mostly from middle schoolers, since.

I can’t speak to the male experience (although my redheaded son will confirm that a few people are still raising small cretins and releasing them into our public schools), but I’ll vouch for all those female stereotypes. Some are explicitly stated by creeps named Tom in seventh grade science, and others simply hover over your shoulders, a cultural jacket you’re welcome to slip your arms into if you wish.

More on that in #3.

2. We’re not being paranoid about the SPF.

At some point, all redheads come to understand that we will never tan. (The exception is those who employ the dubious freckle-fusion method, which kills a dermatologist each time you utter it.) But understanding is not the same as peace.

Historically speaking, we are living through all-time lows in the valuation of both paleness and leg-related modesty. I mean, witch burnings and medical blood-lettings are also experiencing downswings, so it’s a tradeoff, but still: being a pale teen since the advent of short-shorts makes for low self-esteem, generally.

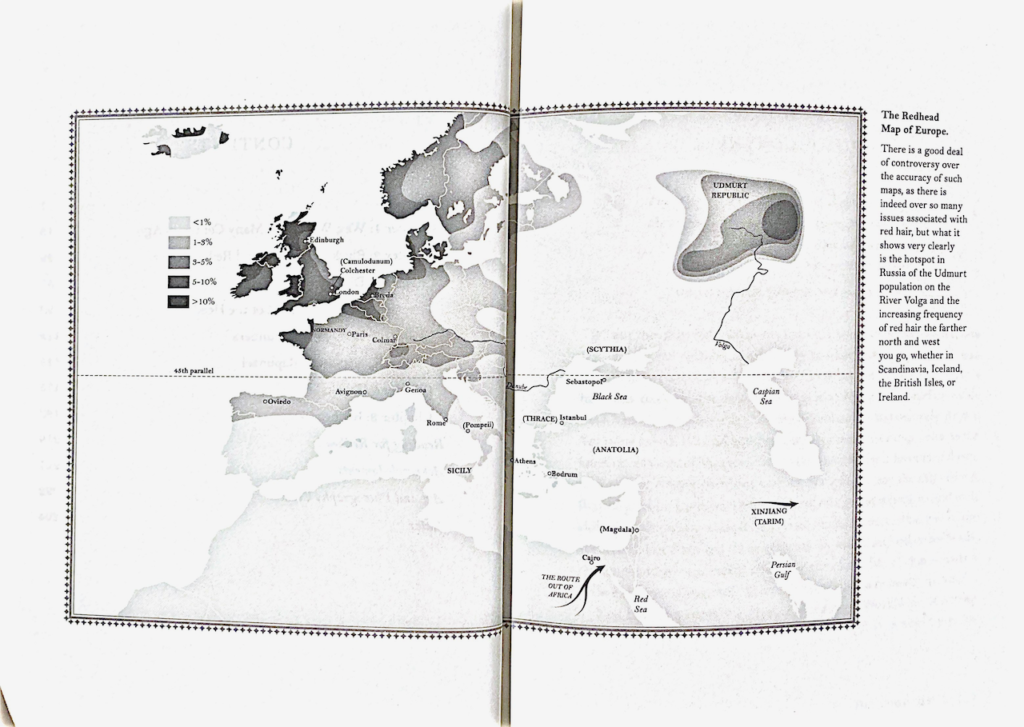

So I appreciated this map at the beginning of Red, where you can see that redheads virtually disappear below the 45th parallel.

Turns out we have a genetic advantage in the dreary north—our pallid complexions absorb Vitamin D like human Shamwows (which leads to sturdier bones, wider pelvises and better fortunes in childbirth)—and so there we thrived.

And any redheads left below the 45th parallel simply DIED OF SUNSHINE.

Sunstroke, Harvey says specifically. But I’m sure melanoma would have finished off anyone who managed to stay hydrated, as our fragile DNA makes us more susceptible to cell damage.

Look, redheads know we’re not fun to be around in the summer. We take a lot of crap for turning down skin-blistering boat rides and shadeless, God-forsaken Fourth of July festivals. But it’s not our imaginations! We’re meant to be wearing sweaters and tending sheep twelve months of the year, and that tube of SPF 100 is the only thing keeping us from extinction. Be nicer to us.

3. Identity is complicated.

So, I don’t like that I’ve never fit the standard of tanned, even-skinned beauty; I don’t like that I was talked into the persona of a wrathful, hot-tempered teenager; and I don’t like that people treat my hair color like it’s public property.

…And yet I don’t know who I’d be as a blonde.

In spite of all the prying and stereotyping, I still use toner to punch up my hair color. So do most redheads you know (the women, anyway), as we tend to slide into a murky brownish-reddish territory after adolescence. And none of us wants to be accused of being brunette.

That is something, when you consider where we’ve been.

Maybe we just like exclusivity. We’re less than two percent of the world population, after all, and that can lend itself to a sense of in-groupness. We’ve all experienced that long moment of eye contact with a passing redheaded stranger, Jeep-driver-style.

But more broadly, maybe our attachment to our red hair is about resilience. Maybe it’s about the way humans can transmute what we like least about ourselves into what we identify with the most.

I didn’t dislike my hair color as a child, but I hated being pale and freckly. I still hate it, really. Because of that, it’s become one of the trustiest implements in my self-deprecation toolbox. If you took it away, I’d feel like I was missing a humor limb. Redhead = pale = joke. It’s fused to my bones at this point.

I don’t think that kind of fusion happens with other hair colors–as Harvey points out, if you dye your red hair any other color people treat you like you’ve stabbed them in the heart–but I do think it happens with other characteristics.

I know for a fact it happens with being short. Probably ditto other physical outliers. Probably ditto personality quirks and odd preferences and whatever else made you either a walking target or a comedic genius on the elementary playground.

You learn to make them your brand. It’s a way to survive the cruelty of childhood, but later, if you’re lucky, it’s a way to be interesting.

Then there’s all the unlearning, too. The taking off and altering of that cultural jacket. Maybe you didn’t have to realize, as I did, that your hair color didn’t actually make you an angry person. But I’ll bet you had to shrug off a bunch of other cheaply made jackets people handed to you in childhood. Jackets that were tailored to you, supposedly, based on what you looked like or who your parents were or how well you could throw a baseball.

How we shape our identities is complicated, friends.

That’s the beauty of all of us humans, I suppose, freckles and all.